CDC expands disease surveillance at major U.S. airports

Topics Featured

U.S. airports host more than 1 billion visitors each year, and it’s not just people. New and emerging bacteria, viruses and other microbes travel through terminals at our major airports every day, and these pathogenic passengers carry with them a wealth of epidemiological knowledge that could inform public health officials about the current and developing state of infectious disease.

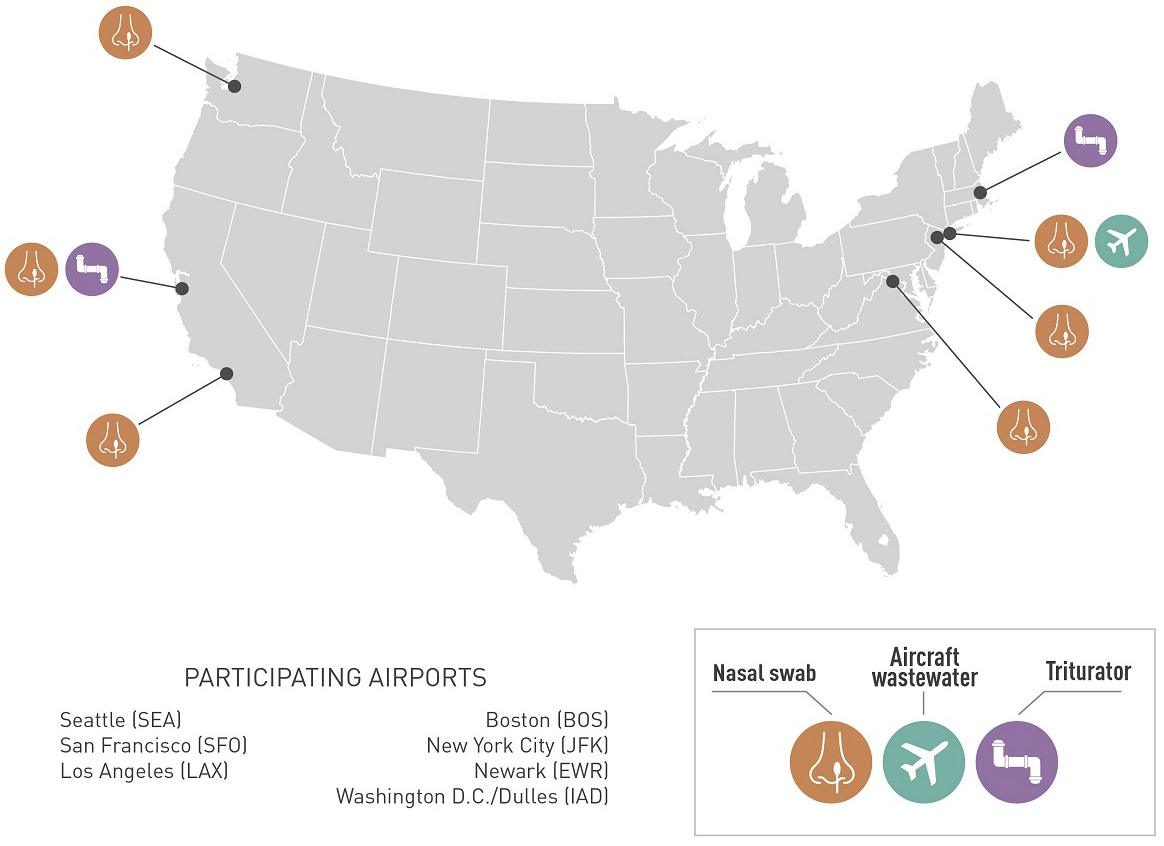

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Travelers’ Health Branch of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention introduced the Traveler-Based Genomic Surveillance Program (TGS) in an effort to detect new SARS-CoV-2 variants in travelers entering seven major airports across the United States (Seattle, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Boston, New York City, Newark and Washington D.C.). While initial efforts relied on nasal samples collected from anonymous volunteer international travelers arriving at the TGS airports, they soon expanded to wastewater testing, where the wastewater from arriving airplanes was tested to genetically identify whether specific pathogens are present. This is a powerful tool – with a single airplane, officials can monitor the disease community within 200 to 300 travelers.

US map of airports in the TGS program. Nasal swab only: Los Angeles, Newark, Seattle, Washington, DC (IAD); triturator only: Boston; nasal swab + triturator: San Francisco; nasal swab + wastewater: NYC (JFK). This map is sourced from CDC.gov.

Now, four of those airports – Logan International Airport (Boston), San Francisco International Airport, Dulles International Airport (Washington D.C.) and John F. Kennedy International Airport (New York City) – will be expanding their test menu to include more than 30 bacterial and antimicrobial resistance (AR) targets as well as viruses such as influenza A, influenza B and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV).

The TGS is hoping that its program growth doesn’t stop with the expanded test menu. Future plans include developing partnerships for country-wide and worldwide wastewater surveillance and enhancing their capacity for surveillance during global mass gathering/migration events.

Please visit the CDC’s Traveler-based Surveillance program webpage for more information on the TGS and its work in tracking the transmission of infectious disease during travel.

How can wastewater predict the future?